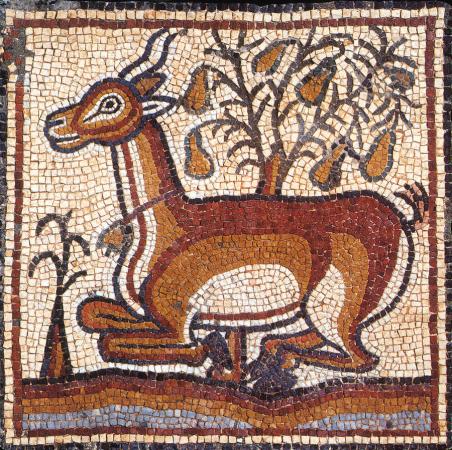

A nation’s tastes and mentality are nowhere more clearly preserved than in its arts. These embody its loftiest ambitions and most telling achievements. Byzantium’s arts clearly reflect the national genius, for the sharp division between religious and secular art did not hamper Byzantine artists; since both flourished side by side, artists had ample opportunity for self-expression. Though there was no place for humour or fantasy in the religious arts, the mosaic floor of the Great Palace proves that both elements found expression in the secular. The scene showing a recalcitrant mule throwing its rider and administering a sharp kick on his posterior as he does so records the incident with delightful malice, whilst the architectural features which appear in the same floor, whether in the form of tempiettas or fountains, reveal an architectural imagination as keen as that which existed at Pompeii. That sumptuous secular arts abounded cannot be doubted. Written records contain many references that testify to the luxury of the imperial apartments in the Great Palace, but these do not deal with isolated cases, for the description of Digenis Akritas’ house and garden proves that private individuals devoted as much thought and care to the settings in which they spent their days as did the emperors.

According to surviving records the empress’s winter apartments in the Great Palace at Constantinople were built of Carian marble, the floors were of white Proconesus marble and the walls adorned with mural paintings of a religious character. In contrast the Pearl

Pavilion, designed for use in summer, had a marble mosaic floor which, in the words of a contemporary, resembled ‘a field carpeted with flowers’; its bedroom walls were faced with slabs of porphyry, green marble from Thessaly and Carian white, while those in the

other rooms displayed hunting scenes executed in glass mosaic. The result was so successful that the room came to be called the Chamber of Mousikos, meaning harmony.

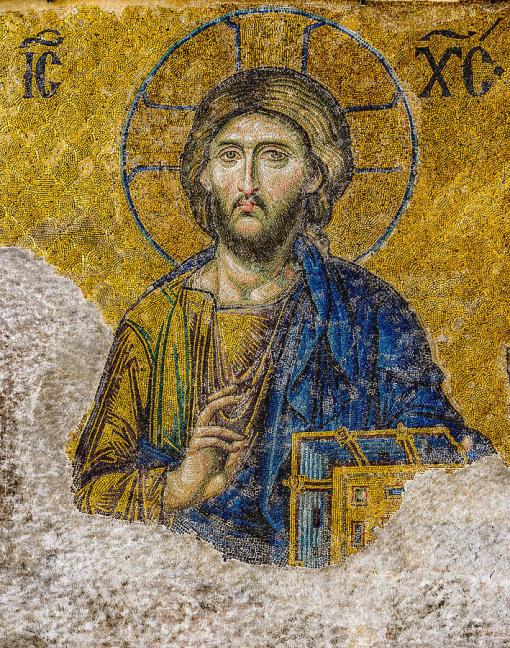

The mosaic floor of the Great Palace is the finest known to us, but future excavations may well reveal further examples of comparable beauty and serenity. Serenity is surely the key which unlocks the door to the magic world of Byzantine art. Byzantine art is not dramatic-even the immense dome of Constantinople’s Haghia Sophia is not at first sight overpowering yet it overwhelms gradually because the art is majestic. Even on the minute scale required for book illuminations, portative mosaics-where each cube is often scarcely larger than a pin’s head-or cloisonne enamel plaques, many of them little more than an inch in size, it retains a monumental quality. Nor is the art when seen at its purest emotional. Instead it is transfused with profound yet restrained feeling. In addition Byzantine art is seldom pretty, yet it is with but few exceptions truly beautiful and admirably suited to its main purpose. Furthermore, it is astonishingly distinctive and could never be mistaken for anything other than itself.

Not the least achievement of Byzantine artists was their ability to develop tentative innovations or minor forms of art into something wholly new and so significant that they became not only major forms of art, but styles which profoundly affected European art of the future. Thus, in architecture, they were responsible for the acceptance of the domed church; in religious painting for the creation of a style, more particularly in icons, which not only greatly influenced the work of the Italian Primitives but also formed the basis of the religious art which came to characterise the Orthodox world; finally, in interior decoration they established the glass mosaic panel as the finest, most opulent form of wall decoration and the opus sectile, or coarser stone or marble geometric mosaic as the most enchanting floor.

At the height of their prosperity the Byzantines relied to a great extent on wall mosaics for the splendour of their church interiors. Immense skill was required for comparable effects to be achieved by means of small glass cubes as by brushwork but they proved superlative masters of this difficult technique.

The art of wall mosaic was not invented by the Byzantines. It had already been tried out in Pompeii and in early Christian Rome where the first mosaics to be set up in churches were placed in the apse. By the sixth century, when the magnificent mural decorations at Ravenna were produced, the art had fully evolved. The techniques consisted in setting glass cubes of appropriate shades and sizes into plaster which was sufficiently damp to hold them in position.

The glass reached the mosaicist in the form of slabs; these were divided into rods which were then cut to the desired sizes, the smallest cubes being used for such sections as eye sockets and the larger ones for draperies or backgrounds. The cubes were made in a vast range of delicate as well as deep colours, together with others where a glass base was covered with gold leaf secured on top by a thin layer of glass; the gold cubes produced a vibrating, shimmering effect admirably suited for backgrounds symbolising paradise. They were so skilfully set by Byzantine artists that the most subtle and delicate compositions were created, the material serving not only to catch and hold the eye, but also to reflect light.

In their religious paintings and mosaics the Byzantines, once again combining those elements which appealed to them from Hellenistic, Roman and Eastern art with their own strongly mystical yet basically earthly conception of the physical appearance of the holy hierarchy, succeeded in transforming the existing idioms into something wholly new. The personages depicted in Byzantine art differ from ordinary human beings both in their physical appearance and in their style of dress. They are clothed in draperies (variants of the classical costume) of the glorious colours which we associate with the sky, whether seen in rainbows or sunsets, because the sky-the abode of these privileged few-is but the floor of heaven. To emphasise the celestial nature of the colours and the ascetic characteristics of the personages the human figures represented in the paintings are considerably elongated. Their faces are not abstracted, yet they are not strictly naturalistic. Their eyes, the mirrors of man’s soul, are greatly enlarged, owing their shape to Egyptian funerary portraits of the opening centuries of our era. The mouth, the vehicle of pain and delight, assumes a form devised by the Byzantines to express these sentiments. The thin, slightly pinched nose is lengthened whilst the faces (furrowed by the suffering endured by those who have mastered the flesh), though initially based on prevailing Greek features, are given a triangular shape in order to express the Byzantine conception of pain. On the other hand the frontal manner in which most of the figures are presented derived from the East. The use of draperies, both as robes and as hangings suspended from two buildings to indicate that the scene is taking place indoors (for no interiors appear in Byzantine art), stem from classical Greece; so too do certain venerable figures, such as Joseph, whose appearance frequently recalls that of an ancient Greek philosopher. On the other hand much of the realism of the art came from Rome, whilst where emotion intrudes into the solemnity of a biblical scene Syrian influence was at work, the dramatic element being absent from the art of Constantinople and Salonica.

Many of the emperors delighted in sculpture. As late as the eleventh century, when sculptures were being produced at the wish of Romanus III (1028-34), Psellus noted that ‘of the stones quarried, some were split, others polished, others turned for sculptures: and the workers of these stones were reckoned the like of Phidias, Polygnotus and Zeuxis’.

Nevertheless, the nation as a whole appears to have been less drawn to that art than to any of the others. This is rather surprising when we remember the legacy left to the Byzantines in this field by ancient Greece and Rome, but the lack of interest is surely to be explained by the fear that statues in the round might lead to a revival of idol worship-a practice which required combating if not within Byzantium’s borders, then at any rate in areas visited by Greek missionaries.

In early times at least the Byzantines had been keen followers of the Roman tradition, not hesitating to erect statues to their emperors and to encourage sculptors to record their features. A number of heads of Constantine I survive. These, like the statue of Valentinian I at Barletta, the head of Arcadius at Istanbul, of Theodora at Milan and of Flacilla, the wife of Theodosius, in the Metropolitan Museum show that they were accomplished portraitists. The earliest of these heads are strongly Roman in style, but though more vital and strongly individualised they are not as perceptive as the later ones. In early times carved sarcophagi were produced. Like the contemporary busts they adhered to classical conventions. The series of fourth-century Sidamara sarcophagi are decorated with scenes of a Hellenistic origin combined with a background of Eastern scrolls. However, by that date the Byzantines had started to prefer plain sarcophagi decorated at most with a monogram.

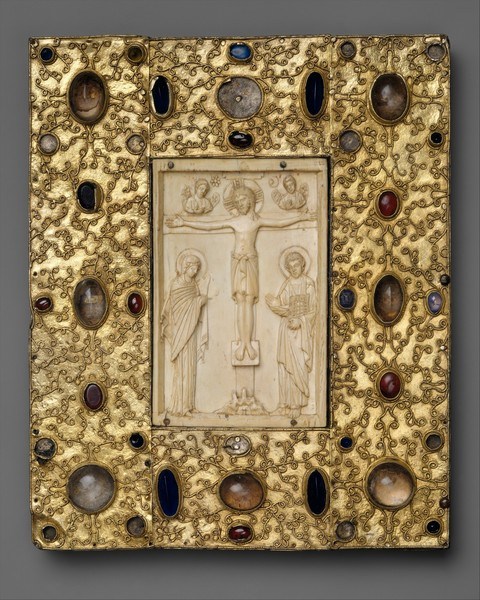

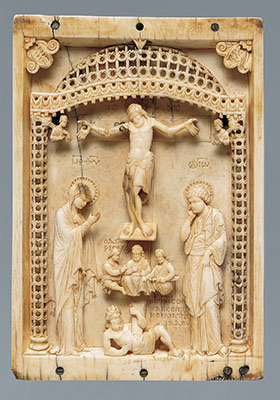

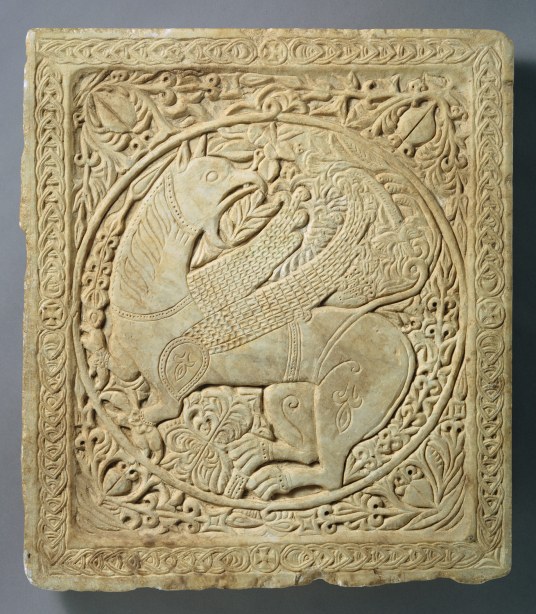

Until about the sixth century the capitals which they used in their churches were executed in an under-cut technique designed to give the abstract, stylised or geometric patterns a lace-like quality which made the design stand out against a dark ground. Especially characteristic of the art as a whole are the slabs on which symbolic or abstract designs of marked distinction appear in low relief. It is, however, to their ivory carvings that we must turn to appreciate to the full the genius of Byzantine sculptors for, although these works are small in size, most are monumental in character.

The carved ivory plaques constituted a most important branch of Byzantine art. Not only Constantinople but, during the early Byzantine period, Milan and Rome in the West, and Antioch and Alexandria in the East were leading centres of the industry. Ivory plaques were not only used by the consuls to announce their appointment but also by those wishing to record their marriage. A fine panel (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London) was made to mark the marriage of a member of the Symmachi family to a Nicomachi. Even more ornate plaques were carved to record coronations. In the fifth and sixth centuries plaques displaying religious designs were fitted together to form pyxes-round or octagonal vessels for holding the Host. At the same time other artists, reacting to the same influences as those which led metal-workers to create designs personifying nations, cities or rivers, adorned their plaques with personifications of Rome or Constantinople. Others preferred to seek inspiration in classical literature, others in genre scenes. The plaques were mounted to form doors, furniture, such as the sixth-century throne of Bishop Maximian (now preserved at Ravenna), jewel boxes, such as the magnificent tenth-century Veroli casket (in the Victoria and Albert Museum), book covers and so on.

Many of the earlier silver dishes, produced in the imperial workshops and stamped with the imperial silver marks, display the same gift for sculpture and the same delight in classical themes as the early ivories. After the fall of the iconoclasts, that is to say, during the middle period of Byzantine art, ornate, lavishly ornamented vessels of a different, typically Byzantine type became fashionable. The decorations on gold, silver or copper gilt ones, and more especially on the Gospel covers, were often executed in the repousse and filigree techniques and enhanced with precious or semi-precious stones, enamel inlays and cloisonne enamels. The latter demanded the utmost skill in their execution. Generally they were made of a gold base, often no more than half an inch across. The technique consisted in attaching wire-like partitions to the base and filling in the spaces with paste, which was then fired to give a translucent effect. The designs chosen for these enamels generally consisted of busts or figures of Christ, the Virgin or some particular saint, though sometimes a floral motif or bird was chosen instead. No less popular than vessels of metal were those in which the body was made of some semi-precious stone such as onyx, rock crystal, alabaster or the like, set on elaborately worked gold stems. Splendid examples of these, in some cases enhanced by the addition of inset stones or enamel, are to be seen in the treasury of St Mark’s at Venice; some of them were probably taken there by returning Crusaders. The earliest Byzantine textiles probably resembled those from Coptic Egypt. During the fifth and sixth centuries the decorations acquired a more markedly Byzantine character. Floral compositions or baskets of fruit, corresponding in style to the decorative sections of the mosaics of Haghia Sophia and of the floor of the Great Palace at Constantinople, were produced in brighter colours than in the earlier stuffs. These designs were often used in conjunction with the Chi Rho and other Christian symbols. More varied techniques and more elaborate weaves had also been evolved by then, the designs being sometimes made by the use of a ‘resist’ substance employed prior to being dyed.

(Source: The Chapter ‘Artists and architects’’ (Pages 211- 229) from the book ‘Everyday life in Byzantium’, by Tamara Talbot Rice)

Research-Selection for NovoScriptorium: Anastasius Philoponus

I absolutely love Byzantine art…thank you so much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Die Goldene Landschaft.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on An Itinerant Scribe and commented:

Interesting post for my Eastern Roman enthusiasts.

LikeLike

Thank you for your extensive art post I reblogged it on An Itinerant Scribe.

LikeLiked by 1 person