Egypt under Greek and Roman rule (from c. 332 BC) was a diverse place, its population including Egyptians, Greeks, Jews, Romans, Nubians, Arabs, and others. In this post we attempt a short presentation on how Graeco-Roman Egypt functioned as a diverse multiethnic, multilingual society and of the legal and political frameworks within which this diversity was organised and negotiated.

Two excellent publications help us learn much on the subject of ‘identity’ in Roman Egypt.

From “Identity in Roman Egypt“, by Katelijn Vandorpe we read, among many other interesting facts, the following:

“The Romans imposed a legal interpretation of the elites, using a strict hierarchical system of ‘Romans’,‘Greeks of the city-states’, and ‘Egyptians’. These labels are no longer linked to ethnic origin: among the ‘Romans’ and the so-called ‘Egyptians’ we find numerous people we would label Greek. These are legal categories and fixed rules determined membership. The Gnomon of the Idios Logos, a set of regulations from the Augustan era but revised afterwards, shows how weak the ethnic basis of these classes was.

Few Romans immigrated to Egypt, and they rarely settled in the countryside. This small group was gradually broadened by individual grants of citizenship to prominent families, whereas Egyptian soldiers received Roman citizenship after their service.

The citizens’ names are identifiers of their class. Romans carried two or three names: the success of the tria nomina pattern (praenomen–nomen–cognomen) was limited in time, and in the Imperial age a two-name pattern became more common (praenomen–nomen or nomen–cognomen). The ‘old’ Roman citizens added the praenomen of their father and their tribus to their dua or tria nomina.

The cives peregrini or astoi were citizens of one of the four Greek poleis (Alexandria, Ptolemais, Naukratis, and Antinoopolis, founded in 130 CE. As under the Ptolemies, one became ‘Alexandrian’ by having citizen parents on both sides and after being registered in a deme (district), the number of which increased under Roman rule. In the reign of Nero a new administrative level was added, the tribe, or phyle.

For Roman law the culturally mixed population of Graeco-Egyptian inhabitants of the countryside were all considered ‘Egyptians’, peregrini Aegyptii or Aigyptioi, although their legal system was Greek in nature, with clear Egyptian influences. They were all subject to the new poll tax (laographia, or capitatio). Within the large subaltern mass of Egyptians, two elite groups were demarcated, who obtained a reduction in taxes: the priestly and the urban class.

The creation of the gymnasial class was a private initiative by people who considered themselves Greeks. It was a continuation of a Ptolemaic group, which was attached to a gymnasium and whose members carried Greek ethnics. In Roman Egypt the gymnasium was still the point of entry into the Greek community and constituted its educational and recreational centre. At the same time, a distinct group who lived in the nome metropoleis was marked off from the villagers by the government. The metropolites and ‘those of the gymnasium’ were fiscally privileged.

Initially, the metropolite group was composed of Greek and Hellenized Egyptian residents of the metropoleis, whereas gymnasial status could be accorded to all those with a father of the gymnasial class and a free-born (Greek or Egyptian) mother. Around 72/73 CE rules for admission were tightened: for the metropolite order, boys had to prove that both father and maternal grandfather were of metropolite status.

The Romans made intermarriage between the urban class and Egyptian peasants unattractive.

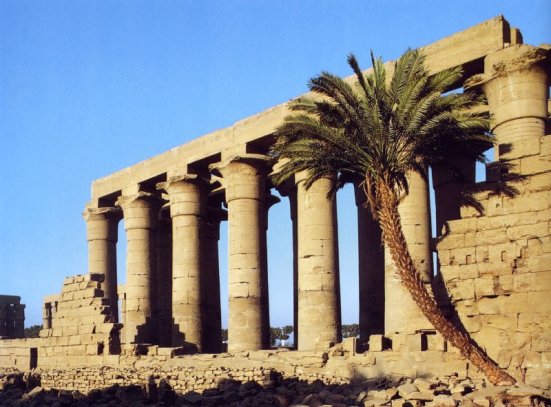

Gradually, the top layer of the urban class tried to compete with the elite of the Greek poleis. Civic benefaction surfaced in Egypt’s metropoleis. Benefaction on a higher level, like the sponsoring of new public buildings or athletic games, was initially only found in the Greek poleis. From about 120 CE, however, civic benefaction flourished as never before and led to a boom in new building projects.

With Severus’ reform of 202, the metropolites were no longer Egyptian ‘barbarians’, but a decade later neither were the free-born Egyptian peasants: through the avenue of the empire-wide Constitutio Antoniniana, they all became Roman citizens. The previous classes disappeared and most ‘barbarians’ in the Greek east assumed the nomen gentilicium Aurelius.

The establishment of a boule, or city council, in Alexandria and in the nome capitals gave birth to a new elite group representing the wealthiest Hellenized urban residents: the bouleutic, or curial, class, formed by councillors (bouleutai) and their families and selected on the basis of their wealth. Membership of the council was a status marker.

Roman citizens could be promoted to equestrian status by the mere possession of the requisite census, without holding a military or procuratorial post.

Under Roman rule, descent was crucial to belong to the upper classes, but some alternative ways for social promotion are attested within the civilian and military milieu for men, women, and their children.

Among the civilians, wealthy euergetai (benefactors) could move up from the metropolite to the Alexandrian class and, eventually, become Roman. According to Pliny’s letters (10.6-7), Alexandrian citizenship was an essential preliminary stage of Roman citizenship, at least in the early principate. Egyptians from the countryside were more or less cut off from social promotion: they could no longer enter the metropolite group when more stringent rules were introduced around 72/73 CE.

The army was an alternative gateway to Roman citizenship, but restrictions hindered upward mobility for the soldiers’ wives and children. Alexandrians who enlisted in a legion became Romans, but legionaries were not allowed to marry during service. Their ‘wives’ had no rights and their illegitimate children did not obtain Roman citizenship, nor could they inherit from their father. Some measures by Hadrian partly resolved the inheritance problems and, finally, Septimius Severus abolished the marriage ban in 197.

Roman rule also had its impact on daily life. Whereas, in Ptolemaic times, Greek immigrants often settled in the countryside, where they established their gymnasia, under Roman rule, compartmentalization was a fact of daily life: members of the urban elite were supposed to live in the city and gymnasia were now only found there. The elite had their rural estates administered through managers. Some papyri suggest that the elite groups disdained the Egyptian mass.

In Ptolemaic times, upward mobility for women was possible by marrying a member of the elite, such as a Greek immigrant, but under Roman rule, local women could hardly marry into an elite class. The impact of Roman rule was to the disadvantage of Egypt’s women, whereas after the Constitutio Antoniniana their position improved considerably.

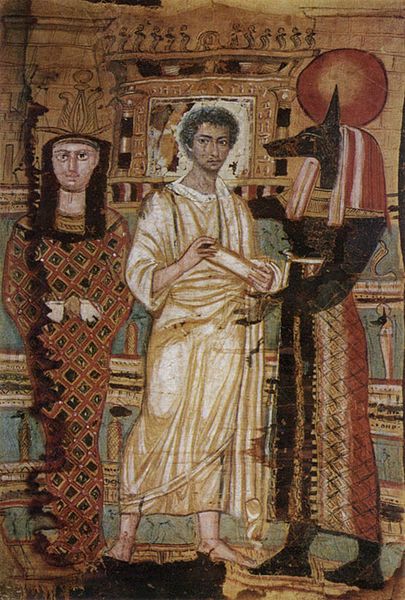

Under the Ptolemies and Romans gymnasia were the educational centres for Greek-minded people, who considered themselves the social elite, though membership came under control of government. Egyptian-minded individuals were in some way connected to the local temple, where ancient Egyptian literature continued, orthey were organized in cult guilds or religious associations. These two spheres (gymnasium and temple) were, though, no longer mutually exclusive in late Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt: Greeks also frequented Egyptian temples, Egyptian religion was ‘Hellenized’, and some priests became part of the urban elite. As a result, the Greek identity persisted, but had an Egyptian colour. Many Egyptians adopted Greek or Roman characteristics in their pursuit of upward mobility.

Graeco-Roman Egypt produced some smaller group associations with an ethnic label, grown out of private initiative. In Ptolemaic times, politeumata of Jews, Idumaeans, or other groups were organizations with a military background, and some were run based on the law of their ancestors. They gave immigrant soldiers a sense of identity in their new country. Politeumata survived into the Roman period, but only as organizations with a purely cultic role, cut off from their military origin.

In general, Roman Egypt tends towards Hellenization.

The native language remained one of the strongest pillars of Egyptian identity. In written documentation, Roman rule ended the bilingual Ptolemaic administration and retained Greek. This language policy had a devastating impact on the Demotic script. As they now needed a Greek summary and subscription, Demotic contracts wasted away at the end of the first century CE. Along with Greek contracts, some Greek customs were taken over by the Egyptians.

Under Roman rule, the priestly elite was privileged in the same order as the urban elite.

Though they had always been the keepers of indigenous traditions, priests were not averse to Greek culture. Religion was outwardly Hellenized.

Under the Ptolemies, some Jews operated within the Greek elite; others had obtained equal rights to the Alexandrian Greeks (isopoliteia) or were part of a politeuma with its own authority and separate organization. But after the Roman conquest, most Alexandrian Jews became de jure ‘Egyptians’ and could only secure some privileges of a religious nature. Jews were no longer part of the privileged class of the foreign conquerors or Hellenes, either in Alexandria or in the countryside. Only individuals who were ready to renounce the Jewish faith could obtain a better status.

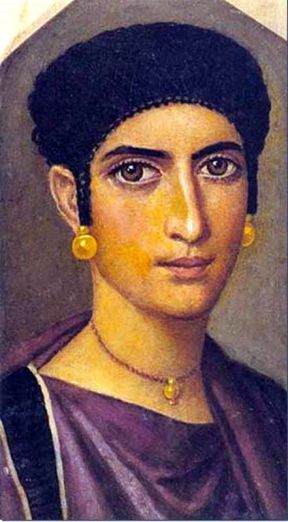

In the Ptolemaic period, the most popular type were Graeco-Egyptian double names, reflecting the two faces of society. As an individual could use either both names or just one of his names, this system enabled people to manipulate their identity and be a Greek or an Egyptian, depending on the context. In Roman Egypt new combinations surface (Roman–Roman, Greek–Greek) and are more popular than ever before.”

From “Women and Gender in Roman Egypt – The Impact of Roman Rule“, by Katelijn Vandorpe and Sofie Waebens we learn much about the impact of Roman rule specifically on women in Egypt. Among many other interesting facts we read:

“The nature of the impact of Roman rule differs depending on the status of the inhabitants.

1) Until AD 212 Roman citizens formed a minority in Roman Egypt. These were higher officials, legionaries, to lesser degree negotiatores and travelers. There were also individual grants of citizenship to prominent families, often Alexandrians, whereas Egyptian soldiers of the auxiliary troops received Roman citizenship only after a military service of 25 years.

2) Roman women in Egypt were, like their colleagues in Italy, subject to the Augustan legislation that stimulated marriage and production of children, as shown by the Gnomon of the Idios Logos, a set of rules from emperor Augustus, but revised afterwards and extant on papyrus.

The citizens of Alexandria and the other Greek cities (Naucratis, Ptolemais and, after its foundation in AD 130, Antinoopolis) were the cives peregrini or astoi and constituted, after the Roman citizens, the upper class of the population in Egypt.

3) The Ptolemaic rulers made a distinction between Greeks and native Egyptians and between Greek laws of the countryside and Egyptian law, a distinction that was, however, difficult to maintain in the later Ptolemaic period, due to mixed marriages and the creation of social mobility that brought several Egyptian people into the classes of the Greeks. For the Roman administration the culturally mixed population of Greco-Egyptian inhabitants of the countryside or chora were all considered ‘Egyptians’, peregrini Aegyptii or Aigyptioi.

The Legal Position of Egyptian Women

Egyptian women had, according to Pharaonic traditions, a strong legal position. They could engage in business transactions without a guardian, they inherited from their father (even real estate), they had to give their consent to marriage, and during their marriage they retained full rights to their property. Greek women in the classical period had hardly any legal independence and were under the control and protection of a guardian or kyrios: their father when they were young, their husband after their marriage, or another relative when they had become a widow.

The Ptolemies respected the Egyptian culture and traditions. They integrated the Egyptian administration into theirs. People, whether Greek or Egyptian, could choose between Greek and Demotic contracts and the Demotic contracts enjoyed the same recognition and validity as their Greek counterparts. These Demotic contracts continued Egyptian traditions, so women did not need a guardian, whereas Greek contracts continued Greek traditions according to which women had to be assisted by a male guardian.

As the dominion of the Greek language had already begun under Ptolemaic rule, the Romans chose to retain only the Greek administration on all levels.

In exactly the same period, new Roman registration rules were introduced for private contracts, which would lead to the disappearance of Demotic written contracts (between 12 BC and AD 2/4). The Romans did not really prohibit, but discouraged the use of Demotic for private contracts in favour of a purely Greek administration and registration.

Demotic notary contracts became increasingly rare, and persisted only for some time in priestly milieus.

With the gradual disappearance of Demotic contracts, Egyptian women had to use Greek contracts and in these Greek contracts, Greek as well as Egyptian women from the countryside had to be assisted by a kyrios or guardian.

About AD 140, under the reign of Antoninus Pius, the procedures concerning guardianship for local women became more stringent than before. Apparently these women now also needed a guardian in cases where previously no guardian was required.

When in AD 212 all free women became Roman citizens, the local women in Egypt became subject to Roman law. Roman law expected the cooperation of a tutor or guardian, according to the Lex Iulia et Titia of Augustan date, to be appointed by the prefect or provincial governor if there was none provided by, for instance, a will. Women had to petition in Latin for the assignment of a tutor.

A tutor, called a “kyrios according to Roman law” in Greek texts, was needed in fewer cases than Greek custom required, that is only in case of transactions involving res mancipi, the most important resources of a family: real estate in Italy (thus, the provincial land in Egypt was not included) and slaves. In addition, a guardian’s consent was required for other legal acts such as the redaction of a will. Contrary to the Greek kyrios, a Roman tutor was usually not a family member.

From about AD 235 onwards, when they had become acquainted with Roman law, they followed Roman rules more strictly and increasingly took advantage of the privilege of the ius trium liberorum, which exempted freeborn Roman women who had borne three children (freed women needed four children) from guardianship.

Third-century Egypt shows a particularity: though women increasingly followed Roman rules, at the same time they often continued their old Greek habits within legal boundaries. Apparently local women preferred to be assisted by a male and Constantine took measures that support this view. Even when guardianship faded away and was abolished, Egyptian women continued their habit of being assisted by their husband in legal transactions and could only act on their own, without the consent of their husband, when they became a widow.

The Romans imposed their own rules on the elite groups by strongly discouraging marriages between different groups, though with some delay. Major changes occurred not only under emperor Augustus, but also in the third quarter of the first century and around 140, under the reign of emperor Antoninus Pius, who apparently introduced a whole set of new rules, which were in general more stringent.

Social mobility for women was no longer possible through intermarriages as was the case under the Ptolemies.”

Research-Selection for NovoScriptorium: Anastasius Philoponus

Reblogged this on Die Goldene Landschaft.

LikeLike

Very interesting article – thank you. Women under the Ptolemies were much freer than they had been in the Athenian democracy. In Idyll 15 of Theocritus, two Greek women living in Alexandria go out into the city. It’s a birds eye view of walking down a main street in ancient Alexandria. The women’s freedom of movement and expression is remarkable, in their home, in public, and later in the palace. 3rd century BCE.

LikeLike