This post is a summary of information on the exciting discoveries made after studying findings from an ancient shipwreck from Tuscany, Italy.

Medical texts written by Pliny the elder and others detail herbal remedies the Romans and Greeks used, but not a lot is known about the contents of individual tablets, says Robert Fleischer, a geneticist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Washington, D.C.

His team obtained the tablets from a shipwreck off the coast of Tuscany that probably occurred between 140 and 120 BCE, based on items recovered from the ship, which was excavated in the 1980s and 90s. Among them was a wooden medical chest stocked with well-preserved tablets filled with what looked like ground plants and vegetables.

To find out what the medicines were made of, Fleischer extracted DNA from two of the tablets and sequenced DNA from the chloroplasts. Among the components were vegetables such as onions, carrots, parsley and cabbage, as well as alfalfa, hawthorn, hibiscus and chestnut – all known to have grown in the Mediterranean at the time, or available to Romans. “All this makes sense,” says team member Alain Touwaide, also at the Smithsonian. Sequencing also turned up a few head scratchers, including a new world plant called helianthus, that probably represent contamination.

(Source: http://blogs.nature.com/news/page/287?by2=Merck)

Fleischer’s initial tests yielded results that Touwaide knew to be flawed. “He came up several times with lists of plants which were highly improbable because they were all plants traditionally thought to come from Asia or the New World,” Touwaide explained. “But last August, he came up with a completely different list of plants because he used the most advanced DNA technology available.”

At first glance, the list may seem more like a recipe for soup than a pharmaceutical formula. Indeed, the tablets are essentially 2,000-year-old bouillon cubes, composed of carrots, broccoli, leeks, cabbage, parsley, onions, radishes and other assorted plants and herbs. But for Touwaide, the fact that most of these items can be found in your average kitchen garden made perfect sense, and reflected the basic principles behind ancient remedies he had gleaned from countless texts.

“When you talk about ancient medicine, everybody thinks about exotic drugs: myrrh, incense, cloves—all these kinds of things,” Touwaide said. “Here we have very simple stuff. That might have been surprising, but not for me.” For early doctors such as Hippocrates, he explained, medicine and food were two sides of the same coin. “In all the writings attributed to Hippocrates, supposedly the father of medicine, half of the formulas for medicines are made out of 45 plants, and these plants are indeed very common. For the Hippocratic physicians, medicine starts with what you eat and is an offshoot of alimentation.”

Touwaide pointed out that, their humble ingredients notwithstanding, the tablets suggest that people were producing sophisticated compound medicines—remedies containing multiple ingredients—earlier than previously thought. “There is a theory about compound medicine according to which they started mainly at the end of the first century B.C. and during the first century A.D.,” he said. “But here we have compound medicines dating back to between 140 and 120 B.C.” In this way, then, archaeological evidence offered new clues about the timeline of medical history that textual sources have not yet provided.

Thanks to two tiny fragments of tablets hidden for two millennia under the sea, for the first time in his career Touwaide could verify that practice corresponded to the texts he had studied. But in his view, this does not necessarily mean that ancient physicians consulted manuscripts the way their contemporary equivalents might look up a drug in the Physicians’ Desk Reference. “It is traditionally believed that texts guided practice,” he said. “I suggest that it’s the opposite—that the texts are a record of practice. Practice was transmitted orally and sometimes written down.”

Fleischer had detected traces of sunflower, a plant thought to have only existed in the Americas until the 16th century. “Fortunately for us, one of the people who participated in the excavation told us that, before going underwater, they put the bottles of oxygen beside the place where they were living,” Touwaide recalled. “This site was filled with sunflowers. So this presence of sunflower in our tablets might be the result of contamination.”

(Source: https://www.history.com/news/ancient-medicines-from-shipwreck-shed-light-on-life-in-antiquity)

Around 120 B.C.E., the Relitto del Pozzino, a Roman shipping vessel, sank off the coast of Tuscany.

Its cargo turned out to have included ceramic vessels made to carry wine, glass cups from the Palestine area and lamps from Asia minor. Archaeologists discovered it also included something even more interesting: the remains of 2,000-year-old medicine chest.

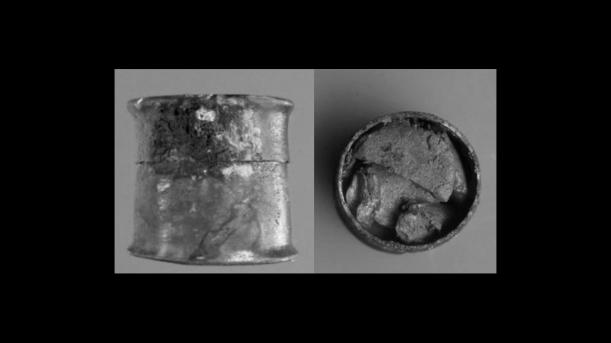

Although the chest itself was apparently destroyed, researchers found a surgery hook, a mortar, 136 wooden drug vials and several cylindrical tin vessels (called pyxides) all clustered together on the ocean floor. When they x-rayed the pyxides, they saw that one of them had a number of layered objects inside: five circular, relatively flat grey medicinal tablets. Because the vessels had been sealed, the pills had been kept completely dry over the years, providing a tantalizing opportunity for us to find out what exactly the ancient Romans used as medicine.

A team of Italian chemists has conducted a thorough chemical analysis of the tablets for the first time. Their conclusion? The pills contain a number of zinc compounds, as well as iron oxide, starch, beeswax, pine resin and other plant-derived materials. One of the pills seems to have the impression of a piece of fabric on one side, indicating it may have once been wrapped in fabric in order to prevent crumbling.

Based on their shape and composition, the researchers venture that the tablets may have served as some sort of eye medicine or eyewash. The Latin name for eyewash (collyrium), in fact, comes from the Greek word κoλλυρα, which means “small round loaves.”

Six tablets were discovered in a tin box onboard an ancient Roman shipwreck, found off the coast of Italy.

Samples of the fragile material revealed that the pharmaceuticals contained animal and plant fats, pine resin and zinc compounds.

“I am surprised by the fact we have found so many ingredients and they were very well preserved considering it was under water for so much time,” said Maria Perla Colombini, professor of chemistry from the University of Pisa.

The shipwreck that the tablets were found on dates to 140-130 BC. It was first discovered in 1974. It is only recently that the tablets have been fully investigated.

“We used a very thin scalpel to detach a small flake of substance to be analysed,” explained Professor Maria Perla.

Mass spectrometry revealed the tablets contained an array of ingredients.

The team found pine resin, which has antibacterial properties. Animal and vegetable fats were also detected, among them possibly olive oil which is known for its use in ancient perfumes and medicinal preparations.

They also found starch, which is thought to be an ingredient in early Roman cosmetics. The team also discovered zinc compounds, which they think may have been the active ingredient in the tablets.

Given the composition of the medicine, the team believe it could have had an ophthalmic use.

Gianna Giachi, from the Superintendence for the Archaeological Heritage of Tuscany, said: “We compared our results with what the ancient authors wrote, including Theophrastus (from 371-286 BC), Pliny the Elder and Dioscorides (both from the 1st Century AD) and we highlighted a large correspondence with the ancient ingredients – especially for the use of zinc compounds.

“In addition, recent scientific literature documents the utilisation in Roman pharmacology of zinc compounds, especially for the preparation of powder used for the treatment of eyes diseases.”

She added that the study, which also involved work by scientists from the University of Florence’s biology department, would help to shed more light on the ancient pharmaceutical world, which was surprisingly sophisticated.

“The research highlights the care, even in ancient times, in the choice of the complex mixture of products in order to get the desired therapeutic effect and to help in the preparation and application of the same medicine,” Dr Giachi said.

In an earlier study of the tablets, a US team carried out a genetic analysis of the plant material in the tablets.

Robert Fleischer, from the Smithsonian’s Center for Conservation and Evolutionary Genetics, found plant extracts including carrot, radish and parsley, which suggested the tablets could have been used for gastrointestinal trouble.

(Source: https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-20937910)

DNA analyses show that each millennia-old tablet is a mixture of more than 10 different plant extracts, from hibiscus to celery.

“For the first time, we have physical evidence of what we have in writing from the ancient Greek physicians Dioscorides and Galen,” says Alain Touwaide of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC.

The box of pills was discovered on the wreck in 1989, with much of the medicine still completely dry, according to Robert Fleischer of the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park, also in Washington DC.

Fleischer analysed DNA fragments in two of the pills and compared the sequences to the GenBank genetic database maintained by the US National Institutes of Health. He was able to identify carrot, radish, celery, wild onion, oak, cabbage, alfalfa and yarrow. He also found hibiscus extract, probably imported from east Asia or the lands of present-day India or Ethiopia.

“Most of these plants are known to have been used by the ancients to treat sick people,” says Fleischer.

Touwaide also hopes to discover theriac – a medicine described by Galen in the second century AD that contains more than 80 different plant extracts – and document the exact measurements ancient doctors used to manufacture the pills. “Who knows, these ancient medicines could open new paths for pharmacological research,” he said.

(Source: https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn19436-2000-year-old-pills-found-in-greek-shipwreck/)

A team of Italian researchers studying the contents of a small tin found aboard the wreck of a second century B.C. cargo ship claim its contents are pills meant to cure eye or skin ailments.

The tin, known as a pyxis was found after excavation of the wreck Relitto del Pozzino between 1989-90.

The pyxis was found among other artifacts (a cup for blood-letting, vials, etc.) that led researchers to believe it belonged to a physician. Inside were small pills, each approximately 4 centimeters across and 1 centimeter thick. Careful analysis in the lab showed that the pills mostly contained zinc – approximately 75 percent – in the form of smithsonite. Other ingredients included animal and plant lipids, pine resin and starch. Because of the nature of their content, the researchers believe the pills were meant to be crushed and dissolved in water and then used as a topical agent to treat eye and skin problems.

(Source: https://medicalxpress.com/news/2013-01-pills-ancient-tuscan-resemble-modern.html)

“This is a fascinating paper on a very interesting set of new finds,” says Richard Evershed, a chemist at University of Bristol in the United Kingdom. He adds that the chemical and microscopic analyses “seem robust, although there are aspects I would have pursued in further detail.” He is less sure that the materials were really used to treat the eyes, though he agrees the case is strengthened by the links to the classical literature.

The tablets were originally thought to be vitamin pills sailors might take while on long voyages. But the researchers have concluded that “the tablets were directly applied on the top of the eyes,” says Erika Ribechini, a chemist at the University of Pisa and a co-author of the report.

Despite lingering questions about the use of the tablets, the study “provides a further example of the high level of knowledge our ancestors possessed concerning the properties of natural materials and technologies required to refine and manipulate them to provide improved products,” Evershed says.

(Source: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2013/01/ancient-eye-treatment-recovered-tuscan-shipwreck)

Abstract In archaeology, the discovery of ancient medicines is very rare, as is knowledge of their chemical composition. In this paper we present results combining chemical, mineralogical, and botanical investigations on the well-preserved contents of a tin pyxis discovered onboard the Pozzino shipwreck (second century B.C.). The contents consist of six flat, gray, discoid tablets that represent direct evidence of an ancient medicinal preparation. The data revealed extraordinary information on the composition of the tablets and on their possible therapeutic use. Hydrozincite and smithsonite were by far the most abundant ingredients of the Pozzino tablets, along with starch, animal and plant lipids, and pine resin. The composition and the form of the Pozzino tablets seem to indicate that they were used for ophthalmic purposes: the Latin name collyrium (eyewash) comes from the Greek name κoλλύρα, which means “small round loaves.” This study provided valuable information on ancient medical and pharmaceutical practices and on the development of pharmacology and medicine over the centuries. In addition, given the current focus on natural compounds, our data could lead to new investigations and research for therapeutic care.

Results To characterize the components of the tablets, some fragments sampled from a broken tablet were divided into subsamples. After preliminary micromorphological examination by light (LM) and scanning electron microscope (SEM), the identification of the inorganic and organic components were carried out with chemical and mineralogical analyses of the subsamples [scanning electron microscope in combination with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray powder diffraction (XRD), and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS)]. In addition, botanical analysis was used to detect the presence of plant remains and their possible origin.

Discussion and Conclusions Hydrozincite and smithsonite were by far the most abundant ingredient of the Pozzino tablet. Although the active ingredient is not necessarily the most abundant, the efficacy of zinc compounds in treating human diseases, known since ancient times, suggests that zinc carbonate and hydroxycarbonate were the active compounds in the formulation of the Pozzino medicine. It is difficult to be sure which Zn compounds were used at the time of the Pozzino. Zinc minerals were generically referred to as “calamina,” a name denoting different combinations of silicate/carbonate/oxide, which could be found in nature, together with ores of other metals, such as Pb, Cu, Fe, or Ag. In therapy, great importance was attributed to zinc oxide, which was artificially obtained during the casting of copper from minerals also containing zinc ores. Pliny the Elder in Naturalis historia and Dioscorides in De materia medica described different qualities of cadmia collected from the vaults or walls of the furnaces during copper production. They wrote how this by-product was useful for preparing medicines for the eyes and for general dermatological purposes.

The linen fibers found inside the Pozzino tablets have not been found in other ancient medicines. The vegetal fibers could have been added to prevent breakage or crumbling of the tablets. Other plant macroremains in the Pozzino tablet included small charcoals. They could have been processing residues of some of the ingredients or have been intentionally added. In fact, black charcoal was found in collyrii from Lyon; however, its role as an active ingredient has not been ascertained.

Starch grains, probably heat-processed, were detected in the Pozzino tablet. Starch with well-preserved helical moieties (amylose) has been found as an ingredient of a Roman cosmetic dated to the second century A.D..

Animal and vegetal lipids were also detected. In terms of the vegetal lipids that may have been added to the preparation, olive oil is a possibility. In the past, oleum acerbum, or “omphacium,” obtained by pressing unripened olives, was specifically used for perfumes and medicinal preparations. The unripened olives’ surfaces might well have been contaminated by olive pollen, which was found in notable amounts.

In ancient times, plant resins played a prominent role owing to their many intrinsic properties. In the case of the Pozzino tablet, the pine resin may have slowed down the natural degradation (rancidity) of the oil because of its antioxidant properties, and it may have reduced microbial growth due to its antiseptic properties.

Finally, the Greek name κoλλύρα, from which the Latin name collyrium derives, means “small round loaves,” highlighting that the shape itself of the Pozzino tablets is consistent with an ophthalmic use.

(Source: “Ingredients of a 2,000-y-old medicine revealed by chemical, mineralogical, and botanical investigations”, by Gianna Giachi, Pasquino Pallecchi, Antonella Romualdi, Erika Ribechini, Jeannette Jacqueline Lucejko, Maria Perla Colombini, and Marta Mariotti Lippi)

Research-Selection for NovoScriptorium: Philaretus Homerides

Leave a comment