“The Imperial war machine was rationally organized, superbly equipped and well trained. There was a large navy, a sort of national guard called the Themata, a professional field army, advanced artillery (including a secret weapon) and sophisticated body of doctrine.

Navy

In the 7th century, Byzantium had the most powerful fleet in the Mediterrean. It was larger, better equipped, organized and trained than any contemporary navy. The empire had reorganized the fleet after the collapse of the western part of the Empire and “the organization of the fleet was an original creation of the Byzantines”. It was led by a “Strategos of the Carabisiani” and two admirals and consisted of around 300 ships. The ships were mostly purpose-built oared galleys, which were ideal in the benign waters of the Mediterrean. The fleet was designed and operated as an offensive arm of the Empire, moving armies and supplies between theatres and around enemy strongholds. The navy was a powerful force to which few enemies could respond.

Army

The ancient Roman system of legions was slowly reformed to respond to barbarian invasion long before the rise of Islam. By the time of Justinian (6th century), the armies of the Empire had been completely reorganized and the principal fighting arm had switched from infantry to cavalry. There were still infantry, but they were part of a type of local militia. The cavalry included both the locals and the elite professional mobile force.

Themata

The new organization was based around the Theme. It was essentially geographic area, which was obligated to train and equip a certain number of soldiers of different types. The thematic armies could be called upon as a sort of militia to protect the local area but would also provide men to aid the Imperial field armies when necessary. The theme usually provided light cavalry to the field armies, but would have a large mix of cavalry and infantry for defense.

The theme system depended on two other sources of troops to fight the wars of the Empire. First were the fedorati, which were a collection of soldiers from satellite states and mercenaries. Most of the fedorati were cavalry, though the most crucial against the Arabs, the Ghassanids were largely an infantry force. The second important source of non-thematic troops was the emperor’s personal army of professional heavy cavalry.

Infantry

Infantry were largely ignored by the Empire, to such an extent that Maurice prefaces his chapter on infantry with “infantry tactics, a subject which has been long neglected and almost forgotten in the course of time.” This is not to say they were not used, but they were largely local forces to provide security in the rear area and movable sanctuary for the decisive cavalry arm.

The thematic infantry was a sophisticated team with a mix of capabilities. There were heavily armed foot soldiers who Maurice states “should have shields of the same color, Herulian swords, lances, helmets”. Unfortunately, by this time the economic might of the Empire could not guarantee all would have armor, so “the picked men of the files should have mail coats, all of them if it can be done, but in any case the first two in the file”. In addition to these armored columns, there were also “approximately one-third of the infantry should be light-armed archers”. These men carried “bows on their shoulder with large quivers about thirty or forty arrows” as well as shields, javelins and spears.

The infantry was organized in regular units of one thousand men which were subdivided several times down to a ten man squad. Each infantry squad was accompanied by it’s own light logistics wagon with “a hand mill, an ax, an adz, a saw, two picks, a hammer, two shovels, a basket, some coarse cloth, a scythe, lead–pointed darts, caltrops tied together with light cords”. This ensured that there would always be adequate equipment to construct defenses and re-arm soldiers who lost or broke weapons during a battle. The thematic infantry, despite neglect by the military bureaucracy was potentially a formidable force.

Cavalry

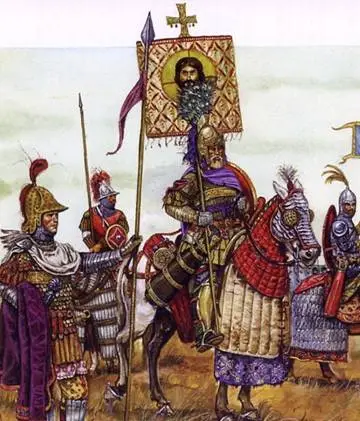

The Byzantine army was built around the mobility of the cavalry. Light cavalry provided by the themes and some fedorati patrolled the vast frontiers and conducted raids against enemies. The Imperial heavy cavalry acted as a strategic reserve and would move to trouble spots as needed.

An unusual mix of light cavalry was recruited from client states and the themes. Mostly they were armed with swords, bows and lances. Particularly famous were the Avar horse archers and the Armenian cavalry. All in all, these were effective forces but they were of variable quality and reliability.

The core of the Byzantine army was the very well equipped and profession Imperial cavalry. This was a multi-purpose force, which could both fight at a distance or charge with shocking force into an enemy army. This force had several names over the centuries, including Scholae, Comitatus, and Kataphraktoi but it was always a highly professional and elite force.

The professional soldier of the Imperial cavalry was the best-trained and equipped warrior of his age. He trained to “shoot rapidly mounted on his horse at a run”. He performed regular formation drills, including wheels and turns with large units. He was protected with hooded coats of mail and helmets and armed with sword, bow and two cavalry lances “of the Avar type”. Even the horses had “protective pieces of iron about their heads and breast plates of iron or felt”. He rode in a saddle equipped with stirrups and solid seat to provide a good platform for fighting. The professional cavalry was expected to have cloaks, tents, and at least two servants with extra horses.

The major drawback to the Imperial heavy cavalry was the cost. The only way a professional force like this could be maintained was to keep it small. Therefore, it was

stationed in central areas of the Empire and deployed as needed to areas of conflict.

The heavy cavalry probably numbered about 40,000 in the mid 7th century, but a large portion was typically kept in the Balkans to suppress the Avars. It is likely that a significant portion of the remainder of these troops were part of the force occupying northern Iraq.

Siege equipment

The Byzantine army built on its Roman heritage and developed sophisticated military engineering and siege craft techniques. They used both tension (bow like) and torsion (catapult) type machines to throw both rocks and bolts. The Byzantine army also used a large swing-arm counter weighted trebuchet, which was more sophisticated than the one used by the Arabs. To support their field armies, the Byzantines had a torsion machine “mounted on carts and swiveling from side to side,” a sort of mobile artillery.

Beyond the creative use of traditional artillery, the Byzantines also had some non-traditional equipment. “Perhaps the best-known Byzantine artillery device is the liquid fire projector”. This “weapon consisted of a tube attached, via a leathern swivel joint, to a sealed canister” which contained a combustible liquid mixture popularly know as “Greek fire”. The clever Byzantine inventors were able to scale the device down to a hand-held flame thrower and up “as a large-scale projector for use on board ship and in sieges.”

Doctrine

(…) The army was organized in a rational and uniform manner based on groups of ten, one hundred, one thousand and ten-thousand men. These units organized and led in a very structured manner with non-commissioned officers, junior officers, field grade leaders and generals. The sergeant, called a dekark or file-leader, led a group of 10 men both in drill and battle. Junior officers were titled Moirarch, and acted both as a deputy to a leader of a column and could lead detachments to perform special tasks. Field grade officers or Menarchs led columns of cavalry or infantry, a unit of 1000 men. A general or Strategos would lead an army of 10,000 men or a combination of several of these with other generals working for him.

Generals served at the pleasure of the emperor, but were career military officers, not political appointees. The need for professional leadership was recognized by Emperor Maurice: “the best general is not the man of noble family, but the man who can take pride in his own deeds”

The two major doctrinal texts that remain from this era show the professionalism of the force. The Strategikon and Treatise on Strategy have detailed chapters on logistics, training, drill and formations, tactics, leadership, combat engineering, sieges, gathering intelligence, command and control, military discipline and punishment of criminals and cowards. They show diagrams of formations and fortifications. They discuss the modes of warfare of principal enemies, the minutia of preparing a march camp and the considerations a general should have when planning a grand campaign. The body of Byzantine doctrine is both sophisticated and informative.

The tactics of the Byzantine army were focused on the professional Imperial cavalry attacking the enemy and using a line of infantry as a refuge. The professional soldiers were also expected to perform flanking movements and to screen the flanks of the formation. There seems to be a distrust of the auxiliary forces, as Maurice places the professionals on both flanks and in the front”

(Source: ARAB-BYZANTINE WAR 629-644 AD, by LCDR David Kunselman)

Research-Selection: Anastasius Philoponus

Enjoyed the article. So much to learn about history, and so little lifetime.

LikeLiked by 1 person